They say an army marches on its stomach. After all, someone’s got to feed the hungry foot-soldiers, right? And this is probably true for any expeditionary group, even an expedition in the name of science. So let’s meet the Indigenous Australian women who fed the scientific Expedition to the Great Barrier Reef in 1928-1929 – Grace Dabah and Minnie Connolly.

Cultural warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are advised that this post contains the names and images of deceased persons.

Sometimes it’s quite challenging to try and write something meaningful about the lived experiences of historical women because so many of them left no written records about themselves. This becomes an even greater challenge when the women in question were Indigenous Australian women. But tiny glimpses of women’s lives can be found, often in unexpected places. In this case, in the mundane accounts of everyday life on a tropical island – on the Greater Barrier Reef Expedition of 1928-1929.

This expedition spent 13 months at Low Isles, off the coast of far North Queensland. Here, scientific personnel from Great Britain and Australia conducted studies into the biological and geological complexities of the reef. The expedition was assisted by many Australians in support roles, including Indigenous Australian workers sourced from the Anglican mission at Yarrabah.

When the scientific personnel arrived at Low Isles on 16th July, 1928, a diary from the expedition, held by the National Library of Australia, notes the following:

“Party landed about 6pm and met by Mr J.E. Young and all occupants of the island – three lighthouse-keepers, their wives and five children. Huts excellent. All luggage landed safely same night and brought across to huts. Cook, houseboy and two children in occupation and appear satisfactory.”

Grace Dabah

The cook, Grace Dabah, the “houseboy” (her husband Andy Dabah), in company with their two children, Edith and Cecil, had been hired (as paid workers) from the mission at Yarrabah. The Dabah family ended up spending four months at Low Isles. By modern standards, it’s very jarring to read of a grown man being referred to as a “houseboy”. Theo Roughley, a short-term visitor to Low Isles, was a little kinder in his description of Andy, whom he considered was the camp’s “general rouseabout”. Some of Andy’s duties would have been to keep the huts tidy, and to take care of sanitary arrangements, but undoubtedly he was proficient at many things, including jobs that others would have undoubtedly baulked at. Journalist and nature writer Charles Barrett nicknamed him “Handy Andy”, and described how Andy expertly scaled a coconut palm to fix the wireless aerial.

Although they were apparently paid workers, the Dabah’s, and the Connolly’s who came after them, were still considered servants at Low Isles. In a post-expedition report, group leader Maurice Yonge wrote of the “efficiency” of these families, but also acknowledged that it was the “cheapness” (of their labour) that had contributed to the expedition’s success.

But it’s from visiting zoologist, Theo Roughley, that we learn what kind of meals the expeditioners ate, and in turn, deduce just how much work was involved for Grace Dabah, who was known in camp by the name “Mrs Handy”. Breakfast began with oatmeal, followed by eggs, boiled, fried, or scrambled (presumably cooked to order as each person preferred) and bacon, or sometimes corned beef. Roughley wrote:

“Mrs (H)Andy (she fully merits the “H”) cooks in the best English style, and her daughter, Edith, waits on the table. And this is no mean task, for there is a family of 18 to wait on.”

Cooking three meals a day for 18 people, with set meal times at 8am, 1pm and 6pm, would have kept Grace very busy indeed. Her daughter’s help with serving meals and clearing the table once the meal was over was probably a necessity. It’s also likely that a fire would have had to be maintained (perhaps by Andy) in order to do the cooking, which would have made it hot work for Grace and Edith.

All fresh food and drinking water had to be brought to Low Isles from the mainland by a motor launch. Charles Barrett wrote that the weekly provisions landed at Low Island included fresh meat, vegetables, fruit, and four dozen loaves of bread! A store contained tinned foods and other emergency rations, in case of bad weather. Zoologist, Sidnie Manton, wrote of occasionally catching fish in a fish trap, and that the “boys” – probably Paul or Harry (boat hands, also from Yarrabah) – sometimes speared coral reef fish; so fish must have been on the menu at least some of the time.

Minnie Connolly

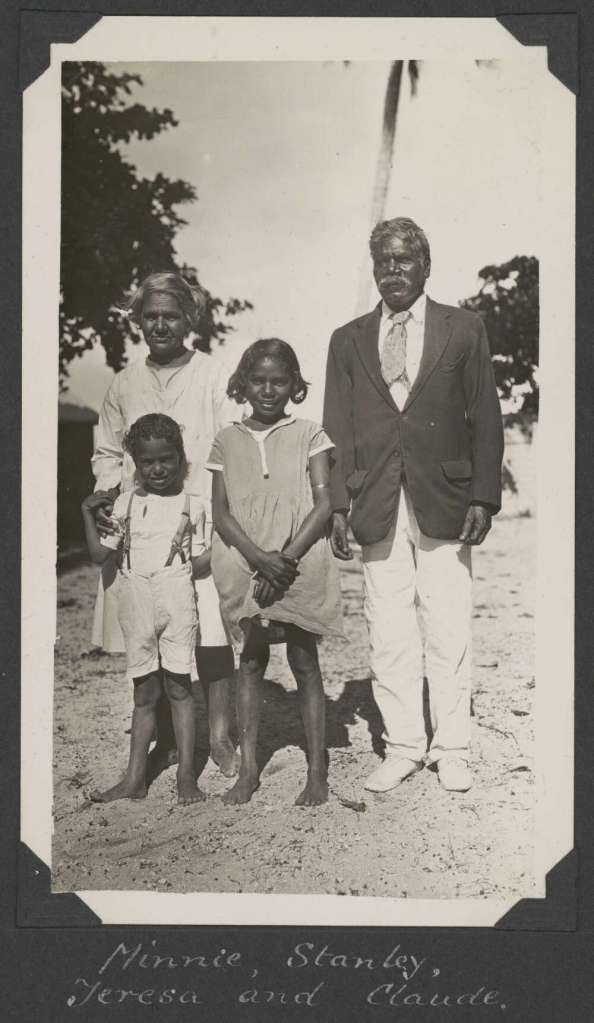

At the end of October, the Dabah family returned to Yarrabah and the Connolly family succeeded them as domestic support for Low Isles. Minnie Connolly (probably then aged around 47) was cook, and her husband Claude Connolly was general camp hand. Two of their children, Teresa (10) and Stanley (5), accompanied them to Low Isles. Apart from a short holiday back at Yarrabah at Christmas, the Connolly’s spent eight months at Low Isles. Three meals a day… prepared for anywhere between 12 and 20 people… every day for eight months. Minnie obviously had stamina.

Mattie Yonge, wife of Maurice Yonge, was the camp’s official “housekeeper” and as such would have overseen the work of Grace and later Minnie. The modern usage of the word housekeeper tends to denote someone paid to do all the household cleaning, but in 1928 it meant that Mattie’s role entailed being in charge of any workers with menial roles, or, to use the terminology of the day – the servants. One of the responsibilities of being housekeeper was to order provisions and maintain stores, and dole out items that needed to be rationed, for example, tobacco. What this means is that both Minnie and Grace – as cooks – probably had little say over what meals they prepared.

But it would have taken skill to prepare meals with limited fresh food and only basic pantry rations and Maurice Yonge wrote that “Minnie was a good cook… [and] was a good worker, and took on practically the entire expedition’s washing – a formidable undertaking.”

There must have been time to make a few luxuries though, and pudding often followed the evening meal, and cakes were made for special occasions. On 4 May, 1929, Sidnie Manton wrote in her diary:

“Had two birthday cakes, one made on the sly by Minnie, Sheina and Mrs Wills and another by Minnie after the arrival of eggs – a great surprise. The one without eggs was rather like fruit and toffee, but very good.”

To celebrate Mattie Yonge’s birthday later that month, the group enjoyed a “feast for tea”, consisting of a meal without any reliance on tinned food, plus an iced cake with fruit salad, followed by some Edinburgh shortbread and chocolates.

These two Indigenous women – Grace Dabah and Minnie Connolly – both deserve to have their names remembered for their contribution to the success of the Great Barrier Reef Expedition 1928-1929.

You can read my new eBook Expedition to the Great Barrier Reef: the story of a ground-breaking scientific mission to Low Isles, Queensland in 1928-1929, and an overview of its legacies, published by James Cook University Library, 2023, at https://jcu.pressbooks.pub/yonge/

Selected sources:

- Manton, Sidnie Milana. Sidnie Manton: Letters and Diaries: Expedition to The Great Barrier Reef 1928-1929. Independently Published, 2020.

- Sir Maurice Yonge papers. National Library of Australia.

- Yarrabah Baptisms 1891-1927, Register of Baptisms, Yarrabah Bellenden Kerr Aboriginal Mission, http://www.cifhs.com/qldrecords/locyarrabah.html

- Yonge, Charles Maurice. “The Great Barrier Reef Expedition, 1928 – 1929.” Reports of the Great Barrier Reef Committee 3, (1931): 1-25.

- Yonge, Charles Maurice. “Report by C. M. Yonge.” Papers of Sir Maurice Yonge, National Library of Australia.

- Yonge, Charles Maurice. A Year on the Great Barrier Reef. London: Putnam, 1930.

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: Low Isles, Low Island, Yonge, Great Barrier Reef, Connolly, Dabah, Yarrabah, Manton, Barrett, Roughley